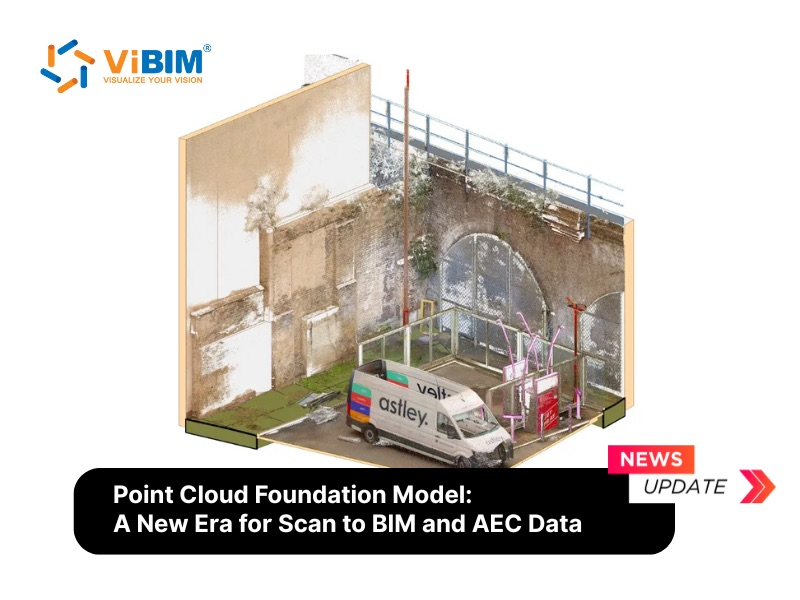

A point cloud foundation model is a large-scale AI system trained on datasets containing millions to billions of 3D points to perform tasks like classification, segmentation, and scene reconstruction. These models learn general spatial representations through self-supervised learning, then adapt to specific applications with minimal additional training.

The technology shows potential to automate time-consuming Scan to BIM tasks: element classification, gap filling from occlusions, and parametric object recognition. Research benchmarks report strong accuracy on standard datasets. But challenges remain—high computational costs, limited construction-specific training data, and accuracy gaps between laboratory tests and real site conditions.

From ViBIM’s perspective, these developments warrant attention but not immediate adoption. Current results come primarily from research prototypes and academic benchmarks. Production-validated tools for construction applications have not yet emerged. We continue monitoring progress while delivering projects through proven methods. Our team has reviewed early-stage AI classification tools and found current accuracy, speed of automated modeling, elements recognition insufficient for production Scan to BIM deliverables.

This article covers the definition and core components of foundation models, comparisons with traditional point cloud AI, key research milestones, potential Scan to BIM applications, current limitations, and practical implications for practitioners. This analysis draws from peer-reviewed research papers published between 2021-2024 and ViBIM’s ongoing technology assessment.

Why Point Cloud AI Matters for Scan to BIM Workflows

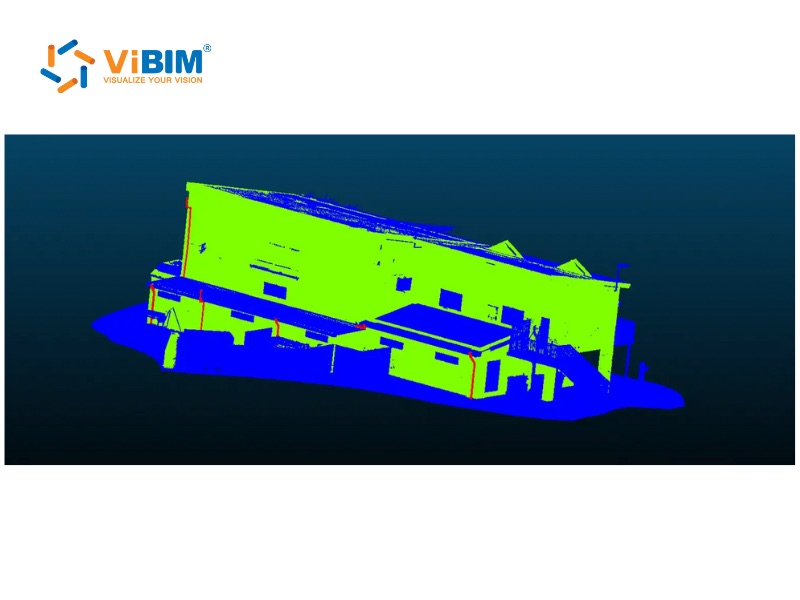

Point cloud AI targets three persistent bottlenecks in Scan to BIM production: time consumption, inconsistency interpretation, and data gaps from occlusions.

Manual point cloud 3d modeling demands skilled technicians to trace geometry, classify elements, and build parametric families. This process is highly labor-intensive and varies significantly by scale. According to ViBIM’s production data, workloads range from under 100 hours for small projects to as high as 2,500 hours for large-scale, complex facilities. Different technicians interpret ambiguous geometry differently—wall thicknesses, pipe diameters, and structural connections vary based on individual judgment. Occlusions from furniture, equipment, or inaccessible areas create missing data that requires estimation or additional scan positions. Complex facilities with dense MEP systems often require multiple scan setups to minimize data gaps.

Point cloud foundation models could address these pain points and advance Scan to BIM automation through automated classification, pattern recognition across multiple scans, and geometric inference for hidden structures. The potential efficiency gains explain why the technology attracts attention from Scan to BIM practitioners despite its current research stage.

What Is a Point Cloud Foundation Model?

A point cloud foundation model is a large-scale AI model trained to interpret and process massive volumes of 3D point cloud data from real-world environments. These models execute diverse downstream tasks such as image generation, scene understanding, and 3D reconstruction.

According to Thengane, Zhu, Bouzerdoum, Phung, and Li (2025) in “Foundational Models for 3D Point Clouds: A Survey and Outlook,” foundation models “synthesize the spatial complexity of point clouds with the reasoning capabilities inherent in large language and multimodal models.” This synthesis bridges the gap between unstructured 3D data and intelligent, actionable applications.

Three components define most foundation model architectures:

- 3D Point Cloud Encoder: This module extracts geometric features from raw point coordinates. Modern approaches use Transformer-based architectures that process point relationships through attention mechanisms. Earlier methods like PointNet used simpler multi-layer perceptrons but struggled with local geometric detail.

- Pre-training Mechanism: Foundation models learn through self-supervised tasks on unlabeled data. Masked Point Modeling—hiding portions of a point cloud and training the model to reconstruct them—is one common approach. This lets the system learn spatial structure without manual annotation, which would be prohibitively expensive at scale.

- Multi-modal Integration: Recent models connect 3D geometry with other data types. Text embeddings allow natural language queries. Image features provide semantic context. This multi-modal capacity enables applications like asking “find all columns” rather than writing custom classification rules.

This synthesis represents the core value proposition: moving from task-specific tools to general-purpose 3D understanding.

How Do Foundation Models Differ from Traditional Point Cloud AI?

Point cloud foundation models differ from traditional point cloud AI in four areas: learning paradigm, architecture, generalization ability, and multi-modal capability. Traditional models like PointNet train from scratch on labeled data for single tasks. Foundation models learn general 3D representations from massive unlabeled datasets, then adapt to specific applications with minimal fine-tuning.

- Learning Paradigm: PointNet requires annotated examples for each object category—chairs, walls, pipes. New tasks demand new labeled data. Foundation models pre-train on diverse 3D scenes through self-supervised learning, then recognize new categories with few or zero labeled examples.

- Architecture: PointNet processes points through permutation-invariant operations but captures limited local context. Foundation models use Transformer-based attention mechanisms that model relationships across entire point clouds, enabling finer geometric understanding.

- Generalization: Traditional models perform well within their training distribution but struggle with out-of-distribution data. A PointNet trained on clean CAD geometry may fail on noisy site scans. Foundation models show broader generalization in research benchmarks, though construction-specific validation remains limited.

- Multi-modal Integration: Classical networks process geometry only. Foundation models connect 3D data with text and image embeddings, enabling natural language queries like “find all columns” rather than parameter-based filters.

The table below summarizes these differences for quick reference:

| Aspect | Traditional Point Cloud AI (e.g., PointNet) | Point Cloud Foundation Model |

| Training Data | Task-specific labeled sets | Massive unlabeled + fine-tuning |

| Adaptation | Retrain for new tasks | Fine-tune or prompt |

| Local Context | Limited | Attention-based |

| Multi-modal | Geometry only | Geometry + text + image |

| Generalization | Narrow distribution | Broader in benchmarks, unvalidated for construction |

These distinctions come from architectural differences documented in recent surveys on 3D foundation models (Thengane et al., 2025).

Key Research Developments in Point Cloud Foundation Models

Three research milestones established the point cloud foundation model paradigm: masked point modeling, unified multi-modal representation, and language model integration.

- Point-BERT (2021) and Point-MAE (2022): These models adapted BERT-style pre-training to point clouds. Point-BERT, developed by Yu et al. at Tsinghua University, introduced Masked Point Modeling—hiding portions of point clouds and training the network to reconstruct missing geometry (Yu et al., CVPR 2022). Point-MAE refined this approach with a simpler Transformer-based autoencoder, achieving 94.04% accuracy on ModelNet40 and 85.18% on ScanObjectNN benchmarks (Pang et al., ECCV 2022). These results demonstrated that self-supervised learning produces useful 3D representations without manual annotation.

- Uni3D (2023-2024): This model unified point cloud, image, and text representations in a single framework. Developed by researchers at BAAI and Tsinghua, Uni3D aligns 3D features with CLIP embeddings, enabling zero-shot classification—recognizing objects the model never saw during training based on text descriptions alone. The model scales to one billion parameters and achieves 88.2% zero-shot accuracy on ModelNet40 (Zhou et al., ICLR 2024).

- PointLLM (2023-2024): Researchers at CUHK and Shanghai AI Lab connected point cloud encoders with large language models. PointLLM responds to natural language queries about 3D objects: “What shape is this?” or “Describe this object’s structure.” In human evaluation, the model outperformed human annotators in over 50% of object captioning samples (Xu et al., ECCV 2024).

The table below summarizes these developments for quick reference:

| Model | Year | Key Contribution | Benchmark Result |

| Point-BERT | 2021-2022 | Masked Point Modeling | 93.8% ModelNet40 |

| Point-MAE | 2022 | Transformer autoencoder | 94.04% ModelNet40 |

| Uni3D | 2023-2024 | Multi-modal alignment, 1B parameters | 88.2% zero-shot ModelNet40 |

| PointLLM | 2023-2024 | LLM integration for natural language | 50%+ human-level captioning |

These benchmarks use datasets like ModelNet40 (CAD objects), ShapeNet (3D shapes), and ScanObjectNN (real-world scans). Construction-specific geometry—MEP systems, structural elements, architectural details—differs substantially from these research datasets. The gap between benchmark performance and construction site accuracy remains untested.

Note: To see how these research milestones are shaping the future of the industry, readers can explore our latest insights on trends in Scan to BIM.

Potential Applications in Scan to BIM Processes

Point cloud foundation models could impact four stages of the Scan to BIM workflow: automated element classification, scene completion, instance segmentation, and semantic query navigation. These applications remain in the research phase with varying maturity levels.

Automated Element Classification

Traditional classification requires manual layer assignment or rule-based scripts. Foundation models with multi-modal capability could accept natural language queries: “identify all structural columns” or “highlight MEP systems.” Early research shows promising accuracy on common building elements in controlled test sets. Complex or unusual geometry remains challenging.

Scene Completion and Gap Filling

Occlusions create missing data in every scan. Current practice requires manual interpretation or additional scan positions. Masked Point Modeling—the same technique used for pre-training—could predict geometry behind obstructions. The model infers likely structure based on patterns learned from training data. Accuracy depends heavily on how similar the target scene is to training examples.

Instance Segmentation

Separating individual objects from cluttered point clouds through precise point cloud segmentation is tedious manual work. Foundation models show improved performance on instance segmentation benchmarks, distinguishing where one chair ends and another begins. Construction scenes with dense MEP runs or repeated structural bays could benefit from this capability.

Semantic Query and Navigation

Rather than zooming and rotating through dense point clouds, future workflows might support queries like “show me the area around the main stairwell” or “find anomalies in the slab elevation.” This interaction model requires reliable spatial understanding that current research systems are beginning to demonstrate.

Each application involves assumptions about accuracy, reliability, and edge case handling that production deployments require. Research papers report benchmark metrics. Site deployments encounter conditions benchmarks do not capture.

Current Challenges and Research Gaps

Point cloud foundation models face six documented challenges that limit near-term production deployment: computational requirements, training data mismatch, accuracy uncertainty, interpretability, integration complexity, and hallucination risk.

- Computational Requirements: Training foundation models demands significant hardware resources—hundreds of GPU-hours for pre-training, substantial memory for inference on dense point clouds. Real-time processing of full building scans exceeds current model efficiency. Edge deployment on site hardware is not practical with existing architectures.

- Training Data Mismatch: Available 3D datasets emphasize indoor scenes, furniture, and vehicles. Construction sites include industrial equipment, temporary structures, and incomplete work that training data does not represent. Domain adaptation remains an active research problem. Models trained on clean research datasets may underperform on noisy field captures.

- Accuracy Uncertainty: Benchmark performance does not directly translate to production accuracy requirements. A model achieving 85% classification accuracy on ShapeNet might produce unacceptable error rates for as-built documentation. The gap between “works on test data” and “reliable enough for engineering decisions” is substantial.

- Interpretability: Foundation models function as black boxes. When classification fails, diagnosing the cause is difficult. For construction documentation with legal and safety implications, unexplainable errors create liability concerns that simpler, more transparent methods avoid.

- Integration Complexity: Existing workflows center on established Scan to BIM software like Revit and Navisworks. Foundation models exist as research code, not production plugins. Integration requires custom development with uncertain maintenance paths.

- Hallucination Risk: Models generating geometry—for scene completion or reconstruction—can produce structures that do not exist. A model might infer a wall where none stands. Human verification remains necessary, potentially negating efficiency gains.

These challenges do not invalidate the technology. They establish the distance between current research and production readiness.

What Could These Models Offer for BIM Data Processing?

Point cloud foundation models could deliver four workflow improvements if research progresses to production-ready status: reduced manual classification time, improved consistency, scalability for large projects, and iterative refinement capability. These remain possibilities contingent on solving current limitations.

- Reduced Manual Classification Time: If foundation models achieve construction-grade accuracy, automated element identification could reduce initial classification labor. Tasks currently taking hours might compress to minutes with human verification. The conditional depends on accuracy reaching acceptable thresholds for each project type.

- Improved Consistency: AI classification applies the same criteria across entire projects. The variability introduced by different technicians interpreting similar geometry would decrease. Model errors would be systematic rather than random, potentially easier to catch through quality control.

- Scalability for Large Projects: Dense point clouds from campus-scale scans strain manual processing capacity. Models that process large datasets without proportional time increases could enable projects that current workflows cannot economically support.

- Iterative Refinement: Preliminary automated results, even imperfect ones, might accelerate human review. Technicians could correct AI outputs rather than trace from scratch—potentially faster if initial accuracy is reasonable.

These potential benefits assume significant progress on current limitations. Timeline for achieving production-ready performance is uncertain. Practitioners should monitor developments without committing resources to immature technology.

What This Means for Scan to BIM Practice Today

Point cloud foundation models are not ready for production Scan to BIM workflows. The research shows promise, but the gap between laboratory demonstrations and field deployment remains wide.

Current Recommended Practice: Continue with established methods: manual modeling in Revit supported by semi-automated QA/QC workflows. While geometry creation remains largely human-led, integrating Revit add-ins, Dynamo scripts, and external validation software accelerates the overall process while maintaining rigorous quality control. Alternatively, utilizing Revit Model Outsourcing services ensures reliable results through these proven hybrid workflows.

Monitoring Approach: Track research publications and commercial product announcements. Look for construction-specific validation studies, not just benchmark improvements. When vendors claim AI-powered features, ask about accuracy metrics on real building scans.

Evaluation Criteria. Future tools based on foundation models should demonstrate:

- Accuracy rates validated on construction data (not furniture or vehicle datasets)

- Clear error handling and human verification workflows

- Integration with existing software ecosystems

- Transparent performance on edge cases and unusual geometry

*ViBIM Perspective

Our experience with traditional AI approaches taught us that research benchmarks often diverge from the multifaceted demands of real-world execution. Practical project delivery requires balancing strict criteria such as processing speed, absolute precision, noise management, and holistic information synthesis—capabilities that current AI models struggle to consistently guarantee. We continue monitoring foundation model developments while delivering projects using proven methods. When validated tools emerge, we will evaluate them against our quality standards.

The technology trajectory suggests eventual impact on our industry. The timeline remains uncertain. Practitioners benefit from informed awareness without premature adoption.

FAQ

Can Point Cloud Foundation Models Handle Large-Scale Data?

Not yet at full building scale. Research models process point clouds with millions of points, but real building scans often contain billions. Current architectures face memory and computation limits at full building scale. Researchers are developing hierarchical and sparse attention methods to address scalability. Production-ready solutions for complete building scans do not exist yet. In the meantime, professionals must rely on optimized workflows for how to manage and transfer massive point cloud datasets efficiently.

What Is the Difference Between a Point Cloud Foundation Model and Traditional Point Cloud AI?

Point cloud foundation models learn general 3D representations from massive unlabeled datasets before adapting to specific tasks. Traditional models like PointNet train from scratch on labeled examples for single applications. The foundation approach offers broader generalization and multi-modal capabilities. Traditional methods remain simpler to deploy and interpret.

When Might These Technologies Be Ready for Production Use?

No reliable timeline exists. Research progress is rapid, but construction-specific validation, software integration, and accuracy verification add years to the path from laboratory to production. Commercial products incorporating foundation model capabilities will likely appear incrementally, starting with constrained applications before expanding to full Scan to BIM automation.

ViBIM specializes in providing a precise Point Cloud to BIM Modeling Solution using Revit and the Autodesk platform. Our team delivers precise as-built documentation for building surveyors and engineering projects. While we monitor emerging AI technologies, we deliver results using proven methods today.

Contact ViBIM to discuss your Scan to BIM requirements and receive a complimentary quote:

- Headquarters: 10th floor, CIT Building, No 6, Alley 15, Duy Tan Street, Cau Giay Ward, Hanoi, Vietnam

- Phone: +84 944 798 298

- Email: info@vibim.com.vn

References

Pang, Y., Wang, W., Tay, F. E. H., Liu, W., Tian, Y., & Yuan, L. (2022). Masked Autoencoders for Point Cloud Self-supervised Learning. European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV 2022), pp. 604-621.

Thengane, V., Zhu, X., Bouzerdoum, S., Phung, S. L., & Li, Y. (2025, January 30). Foundational Models for 3D Point Clouds: A Survey and Outlook. arXiv preprint.

Xu, R., Wang, X., Wang, T., Chen, Y., Pang, J., & Lin, D. (2024). PointLLM: Empowering Large Language Models to Understand Point Clouds. European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV 2024), Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 15083.

- arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.16911

- Project Page: https://runsenxu.com/projects/PointLLM/

- GitHub: https://github.com/OpenRobotLab/PointLLM

Yu, X., Tang, L., Rao, Y., Huang, T., Zhou, J., & Lu, J. (2022). Point-BERT: Pre-training 3D Point Cloud Transformers with Masked Point Modeling. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2022), pp. 19313-19322.

- arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2111.14819

- CVF Open Access: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content/CVPR2022/html/Yu_Point-BERT_Pre-Training_3D_Point_Cloud_Transformers_With_Masked_Point_Modeling_CVPR_2022_paper.html

Zhou, J., Wang, J., Ma, B., Liu, Y. S., Huang, T., & Wang, X. (2024). Uni3D: Exploring Unified 3D Representation at Scale. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2024), Spotlight presentation.

- arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.06773

- OpenReview: https://openreview.net/forum?id=wcaE4Dfgt8

- GitHub: https://github.com/baaivision/Uni3D